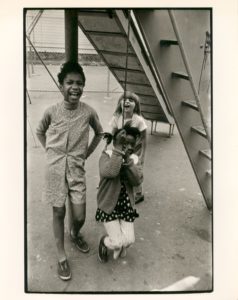

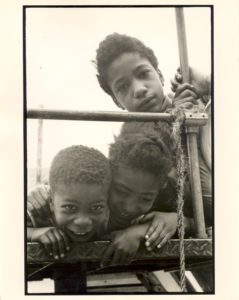

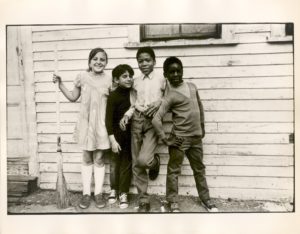

About 1/2 mile southwest near Gallagher Terminal, once stood a neighborhood called Hale-Howard for its cross-streets. It was home to many Black, Puerto Rican, and Jewish families. In the 1970s, Lowell demolished it for Urban Renewal. At first, 100 affordable home units were to be part of the redevelopment, but by 1972, it was declared “all industrial.” Although this was a tight-knit community, families were forced out. In an oral history, a former City Councilor suggested he thought racism was a factor in this decision. The removal of this neighborhood is an example of how Black Lowellians faced discrimination through housing.

More of the Story

Hale-Howard, occupying an area of the city near the current Lowell Regional Transit Authority hub, suffered the same fate as Little Canada and the Triangle Acre. A Jewish neighborhood for nearly seventy years, its name was derived from two perpendicular streets—Hale and Howard—running through the area. The streets contained numerous institutions and stores that defined the neighborhood, including two Synagogues, several bakeries, and delicatessens. Personal descriptions provide a wealth of understanding and insight into the area. Robert Malavich, long-time Lowell city planner, recalled Hale-Howard:

There were a lot of Jewish people in that neighborhood … And we’d drive by these tenements and I had friends who lived in some of those and knew that—you know, in hindsight I knew that they were bad, but while I was there and visiting, it was just like anybody else’s house.51

For Malavich, the essential element was that the people living in what became the demolished area had their lives changed forever. In the 1970s, Lowell’s City Development Authority (CDA) controlled renewal projects. It cleared designated parts of the city, turning them into industrial parks and commercial centers. To some extent, the CDA acted as a “relief valve” for the mayor, the city council, and the city manager because appointed members, not elected officials, ran it, making the process less politically risky. Indeed, former councilor and CDA appointee Robert Kennedy contended that the Hale-Howard and Northern Canal (Little Canada) demolitions would not have happened absent such a political buffer.52 A 1972 CDA publication focused on citizen participation in renewal projects.

The experience of the past is that very little citizen participation occurred in the renewal projects of the city, and, in fact, very few community organizations were in operation in Lowell at that time. The outcome was that project area residents were not formally involved in the decision making process, and development plans may or may not have reflected the values and goals of area residents.53

In 1968, because of the outcries across the country from citizens dislocated by renewal activities, HUD had mandated the creation of Project Area Committees composed of neighborhood residents for all new renewal projects.54 In December 1968, the CDA held an election in the neighborhood and formed the Hale-Howard Advisory Committee (HHAC). Of the 390 eligible voters in the neighborhood, 68 cast ballots and thirteen members were elected. According to the CDA, the group “served as an information dispensing organization regarding administrative progress on the project and as an occasional forum for citizen discussions.” More than anything else, the group sought community buy-in to the project. However, Community Teamwork, Inc. organized a rival organization called the Lower Highlands Neighborhood Council (LHNC) among residents in and adjacent to Hale-Howard.55

Neighborhood relocation started on March 12, 1971 when the CDA received authorization to dispense benefits to 158 families living in the target area. They also had to find housing for low-income families being displaced in a city already pressed to find housing for its residents.56 CDA Executive Administrator James F. Silk reported that in June 1972, fewer than a dozen large families lived in the targeted sections of Hale-Howard. Smaller families found apartments themselves or with minimal CDA help. However, these large families encountered considerable trouble finding adequate housing.57 A June 1972 Lowell Sun article highlighted the problems experienced by families with seven or more children. The CDA offered public housing to the families, mainly in the Bishop Markham development, the only public housing that could accommodate large families. But even Bishop Markham couldn’t house all of the families being forced from their neighborhood. According to the CDA Relocation director, “I would describe the shortage as not being acute but rather typical of the average city that is struggling to rebuild and revitalize itself.”58

With the demolition date approaching, pressure mounted to relocate the families. Using federal payments, the CDA moved 104 of 158 families from the neighborhood. Forty families moved to apartments across Lowell, ten families moved into publichousing, and 31 homeowners found new homes.59 Relocation assistance included help with leased housing and rent supplements. Payments averaged $10,600 per family, $4,400 below the $15,000 maximum allowed. The CDA paid that sum in addition to fair market value to all homeowners forced from the neighborhood.60

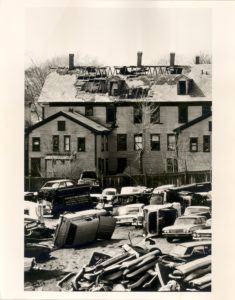

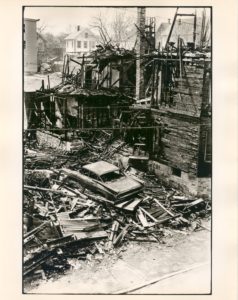

Going forward with the demolition, city officials argued that the Hale-Howard neighborhood had experienced too much neglect to be turned around. To be sure, the working class neighborhood was not in good shape, yet the demolition planning created a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the Lowell Sun documented, conditions deteriorated rapidly from the time the neighborhood’s fate was first discussed in the early 1960s through the first demolitions eleven years later in 1971. Over the years, “People moved out, tenement houses became abandoned, and the once old proud neighborhood became a slum area, almost a ghost city by the turn of the decade.”61 While the city and the CDA discussed Hale-Howard’s future, residents fled, the infrastructure decayed, and landlords stopped investing in their properties.

In a final twist, as the relocation efforts wound down, the CDA and the Council altered the original plan. At first, the LHA had agreed to build 100 new housing units on 3.5 acres of the neighborhood set aside for the purpose. Now, the housing component was eliminated. In early June 1972, the Lowell Sun reported that the CDA had declared the 3.5-acre site “inappropriate for residential use” and, in a move that alienated many early supporters, the cleared site was to be ‘all-industrial’. The city council, City Manager Jim Sullivan, and “nearly all city officials” supported the change, but Councilor Armand Mercier recalled that during the controversy Brendan Fleming and Richard Howe, Sr. won seats on the council by campaigning against the Hale-Howard demolition.62

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development opposed the change to an all-industrial site. In 1971, it had approved a plan to convert four parcels in the neighborhood, three of them city-owned, into housing. The CDA decided to turn the neighborhood into an all-industrial site.63 According to city planners from that era, the decision was an easy one because their priority had shifted from housing creation to job creation, likely on the advice of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor who worked as a city consultant on the project.64 The assumption was “there seemed to be enough housing in the community.” Instead of rebuilding the neighborhood, plans shifted to the construction of an industrial park, some demolition, and some rehabilitation of existing properties.65

Other factors influenced the decision to move to an all-industrial zone, including that the public from outside the neighborhood supported the job creation mission. Armand Mercier suggested another reason for support—racism. According to him, visions of low-income housing had Lowellians, “visualizing people coming in from Roxbury,” nearby Boston’s large African-American neighborhood.66 HUD withheld final approval for the project until the CDA and LHA provided a tenant-by-tenant account of relocation plans and completed the proper relocation of the families living in the neighborhood as of July 1972. At the time, CDA needed to relocate 41 families and half of the neighborhood’s businesses.67 When HUD’s conditions were met, the project turned into an all-industrial development.68

All photos are from the Tyrrell Richard Schein Collection